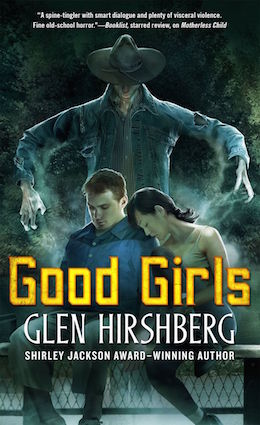

Glen Hirshberg’s Good Girls—available February 23 from Tor Books—is the standalone sequel to Motherless Child.

Reeling from the violent death of her daughter and a confrontation with the Whistler—the monster who wrecked her life—Jess has fled the South for a tiny college town in New Hampshire. There she huddles in a fire-blackened house with her crippled lover, her infant grandson, and the creature that was once her daughter’s best friend and may or may not be a threat.

Rebecca, a college student orphaned in childhood, cares for Jess’s grandson, and finds in Jess’s house the promise of a family she has never known, but also a terrifying secret.

Meanwhile, unhinged and unmoored, the Whistler watches from the rooftops and awaits his moment.

And deep in the Mississippi Delta, the evil that spawned him stirs…

1

In the heart of the hollow, at the mouth of the Delta, the monsters were dancing. Their shadows slid over the billowing green walls of the revival tent, rolling together, flowing apart. To Aunt Sally, rocking and smoking in her favorite chair in the shadows of her pavilion tent out back, their movements seemed hypnotic, lulling, like nimbus clouds across the moon, rainwater down glass. They kept her company, the shadows did. They were all the company she had ever kept or needed. Looking past the hollow down the mossy bank, she could see the moon out for its nightly stroll down the slow-sliding surface of the Mississippi, through the clustered cattails, the swamp roses, and spider lilies. As she watched, the moon seemed to turn, as it did every night, and nod in her direction.

Howdy, neighbor. Mind if I smoke?

Almost peaceful, Aunt Sally thought.

Except that someone—one of the younger monsters—had gotten hold of the stereo in there, under the big tent, and unleashed some of that shuddering rumpus music. Thunder-and-swagger music. It didn’t last long, Caribou saw to that. Just long enough to put a big jagged crack right down the center of the evening. Break the mood. Remind Aunt Sally just how far from peaceful she’d been feeling lately. How very, terribly bored.

Probably, she thought, she should try to remember some of the younger monsters’ names, although the truth was, she couldn’t imagine what for. Had she even known their names when she’d made them? She couldn’t remember, now, but suspected she had. All she could remember with any certainty was the surprise, every time, when it did happen. When they sat up after she had finished, patting in wonder at what ever holes she’d torn in them. And she remembered her delight for them, or maybe simply for what she’d done. She’d always assumed she would understand what made it happen, someday: the transformation instead of dying, or after dying. Some of it, she knew, was simply that she’d wanted it to happen. But she never had quite figured it out. Neither had Mother, or any of the very few others who’d achieved it, accidentally or otherwise. And the fact was, Aunt Sally had stopped worrying or even wondering about it a long, long time ago.

Should she tell Caribou she had taken a secret liking to a little thunder-and-swagger music from time to time? The idea—the look of horrified disbelief, of shattered sensibility she could already envision on his gaunt, luminous sickle-moon face—made her smile, faintly. At least, she was fairly certain that she was smiling. According to Caribou, her mouth never moved, these days, except when she was Telling, doing Policy. Not even when she ate.

The music reverted to old, familiar favorites. No drums, no guitars, just a piano and a muted trumpet loping and leaning, ducking and bobbing. Victoria Spivey moaning and sighing, surrounded by snakes. That song, too, had sounded like shuddering rumpus back in its day, when Victoria Spivey had played it. Way back when Aunt Sally used to dance, too, instead of sitting out back watching the dance. When she did for herself, instead of for others. Back when she and Mother used to light out for the shacks, the little towns, the helpless husbands and sad, hungry boys, on the best, most memorable nights. The two of them twisting and spinning, in a sweatbox-cabin full of people who sweated and spun wherever she and Mother spun them.

She did miss that, sometimes. Occasionally. The doing for herself. More, she missed Mother, although that word—“miss”—wasn’t the right one. Aunt Sally did not “miss.” She simply remembered.

And because she remembered, she wondered, from time to time, exactly where Mother had gone and got to, now, with that weedy little monster she had somehow made—how had that happened? Why had that happened?—and then gotten herself addicted to. Foolish Mother. Gone these so many years. How many, now?

Aunt Sally blew smoke through her motionless mouth, the cloud of it closing over the starlight, spreading thin, dissipating. In the cattails down-hollow, frogs bleated, cicadas sawed. All the night creatures, humming their hunger. She watched the tent, the shadows on its rippling walls. Too many shadows. For the first time since… oh, when? That year the Riders came down here, created some rumpus of their own, got the whole countryside so stirred up and boiling and ripe? For the first time since then, Aunt Sally found herself musing on the world out there, just on the other side of the cane fields and pecan trees. Full of people to set spinning. Not that they’d spin any differently than the ones here did.

How many of the dancers in that tent, she wondered, watching the walls, actually were hers, were creatures she had made? Caribou, of course, but the others? Any of the others, come to think of it? Maybe she couldn’t remember their names because they weren’t hers, after all. Maybe all of hers—and there hadn’t been so very many, truly—had long since left her side. The thought jarred, even alarmed her, a little.

Was that true? It could be true.

Drawing her shawl tighter on her cold, cold arms, Aunt Sally pushed her bare feet into the night-wet grass and set her chair rocking. Had Mother been her last? Sometimes, Aunt Sally forgot she had even made Mother. Certainly, she

hadn’t meant to. What God There Was—which was what she had always called what ever God there is—had apparently sensed that she needed a companion, was going to die of boredom or loneliness without one. And for once, What God There Was had shown mercy, fulfilled a wish she hadn’t realized she was wishing.

Or else—more likely—He’d sat up there in His hollow, outside His own tent, watching the shadows He had made. He had gazed down the years and seen a new opportunity, a whole new sort of suffering he could inflict on His long-suffering Sally: He’d give her a companion. And then her companion would leave her.

So in the end, was any of it her doing? His?

Either way, it had happened. She had been bored, lonely, both. So bored and lonely that she could no longer imagine herself before or after boredom or loneliness. And then she had found Mother and made her.

Maybe that was what happened in those moments. Maybe the changing really was caused or catalyzed simply by need, when the need was strong enough.

Or maybe when the need was most reciprocated? Or did the process require a specific sort of need, at a specific time? Or was it chance? Luck?

Policy?

To herself, rocking in the grass, watching the moon vanish downriver, Aunt Sally snorted. Smiled. Thought she smiled.

Where was Mother now? Still chasing her Whistling fool, no doubt. And Aunt Sally had to admit it: her fool really could Whistle, and also sing. How many years could singing and Whistling fill? More, apparently, than sitting in her chair, just there, beside Aunt Sally, rocking together, listening to the cranes and alligators in the swamp. Watching their children grow.

The flap at the back of the revival tent parted, and Caribou emerged, white as moonlight, long as a river-reed, eyes round and dark and skittish as a deer’s. He stopped a moment before approaching, settled his white tails-coat on his hanger-thin shoulders, straightened his bow tie. To Aunt Sally’s surprise, he had a companion in tow. She’d seen this one before, of course, but not for a while. She thought she might have known his name, once, but hadn’t the slightest idea of it, now. What did it matter?

And what could he possibly want or wish for that Caribou would believe she might acknowledge or grant?

“Tuck your shirt in,” she heard Caribou say.

His companion—bearded, in a flannel work shirt that looked warm, to Aunt Sally, comfortable, yes, she liked that shirt—mumbled out of his drunken mouth. But he risked a single glance in Aunt Sally’s direction, caught sight of her, and did as he was told.

How long, Aunt Sally wondered, since she had even spoken to any of them but Caribou? Were they stopping coming to her? Forgetting she was out here, even? Surely not. But the nights did keep stretching out, now, spooling away down the grasslands, slow and muddy as the Mississippi, bored by their own movement, moving anyway. With a sigh, she waved a hand at Caribou, the sign to approach.

“Your stocking’s down again,” Caribou said to her as he stepped out of the moonlight, under her canopy, into her circle of shadow. And Aunt Sally sighed again, this time in something like contentment. It was Caribou’s voice, more than anything, that she enjoyed. That impeccable tone. Groomsman, servant, grandson, lover, all at the same time. Her lily-white Man of the South, who did whatever she told him.

It had bored Mother, that tone. Mother liked her lovers louder, or full of music.

“So pick it up,” she snapped.

Caribou’s mouth twitched—in delight, controlled delight, he knew she preferred his exasperation—and he started to raise one of his ridiculously long arms in protest. Then he dropped to one knee to fix her stocking. Aunt Sally smiled. Thought she smiled. She ignored Caribou completely, pretended to focus on his companion. Silly devil-goatee beard, big fat bruise on his pasty-white cheek, as though he had been fighting. Abruptly, she did remember something about this one: he had a tattoo of a wasp on his neck. There it was, when he dropped and tilted his head to keep from looking at her too directly, seemingly crawling up his throat toward his ear. Right where she had told him his dream said he should get it. Gullible, pasty goatee-moron.

“Aunt Sally,” he said, all respectful and proper, the way Caribou always told the ridiculous ones they had to be. “We’re hungry. And tired.”

Again, she sighed, feeling Caribou’s fi ngers crawling up under her skirt, reattaching her stocking. Lingering, not lingering? He liked her to wonder. She liked him to wonder if she did.

“So you’re speaking for all of them, child?” she purred, and whatever Caribou’s hands were or weren’t doing under her skirt, they stopped. He looked up from under his elegant, artfully gelled swoosh of blond hair, like a baby anticipating a story.

Well, Aunt Sally couldn’t resist that. Never could. She smiled—thought she smiled—at the wasp-goatee man, and patted Caribou on the top of the head, let her fingers spread along his scalp, through all that beautiful, beautiful blond.

“It has been awhile,” she said.

“Yes,” said Wasp-goatee, all mesmerized. “We were all saying so.”

“And the nights do get long.”

“So long.” The moron’s voice, his whole body, quivered.

“And you think it’s time for a Party?”

Under her skirt, Caribou’s hands tightened on her thighs. Then they started sliding up. He couldn’t help it, poor boy. He was so utterly hers, always had been. He gazed up at her from way down deep in his hypnotized deer-eyes. “Yes,” he said. “Aunt Sally, let’s. It has been so long.”

“It has,” she said, and closed her legs. She shoved Caribou back, hard, on his haunches, and grabbed the gaze of the goateed one, held it until he started to sway. “A Party. We’ll need some guests.”

“Guests. Yes,” said the goateed one.

Once more, Aunt Sally thought of Mother. She wondered if she could get word to her, somehow. Invite her to a celebration, in honor of her return home. Preferably without her Whistling fool, though she could bring him, too, if she had to. Either way, maybe Mother would come. Maybe she would stay this time.

Aunt Sally smiled. Thought she smiled. “Good. Well, then. In that case.” She stretched out her own beautiful long-fingered hands, nodded at Wasp-goatee. “Come here, son. Tell Aunt Sally what you’ve dreamed.”

2

Rebecca, come on,” Jack said, leaping free of his spinning chair in mid- spin to alight in front of her. He spread his arms, grinned, and the suction-cup dart sticking out of his forehead waggled like an antenna. “Do the thing.”

Beside Rebecca in the next cubicle over, Kaylene’s stream of muttering intensified. “Come here, little Pookas. Come here, little Pookas, comeherecomeherecomehere…” Her fingers punched repeatedly at her keyboard, and out of the tiny computer speakers came the twinkling music and popping sounds that accompanied so many of Rebecca’s nights working the Crisis Center, as Kaylene’s Dig Dug inflated and exploded her enemies.

“Comeherecomeherecomehere SHIT!” Kaylene, too, leapt to her feet, joined Jack in front of Rebecca’s desk. Her beautiful black hair had overrun its clip, as usual, and poured over her face and shoulders.

“Tell Rebecca to do the thing,” said Jack, grabbing Kaylene around the waist and glancing over his shoulder. “Marlene, put the book down, get over here.”

“Rebecca, do the thing,” Kaylene said. “MarlenePooka, don’t make me come over there.”

In the far corner of the room, where she always set up so she could study but never stayed, Marlene sighed. She stood, straightened her glasses, put a hand through her red-orange, leaves-in-autumn hair. Not for the fi rst time, Rebecca felt a flicker of jealousy about Marlene: too much work ethic and hair color for any one person. Especially a person who could barely be bothered to comb all that hair, let alone care about it, and who also knew when it was time to put the Advanced Calculus and Cryptography textbook down and come help her closest friends bug her other closest friend.

Then, as always, Rebecca’s jealousy melted away as Marlene took up her position, linked arms with Jack, and grinned down at Rebecca, still seated at her desk with the Campus Lifeline Crisis Center manual she knew by heart tucked right where it belonged against the special blue Campus Lifeline phone, complete with idiotic life-preserver logo. Rebecca watched them beam down at her. Jack and the ’Lenes.

For an awful, ridiculous second, she thought she was going to burst into tears. Happy tears.

“Rebeccccaaaaa,” Jack chanted, and the suction- cup dart on his forehead bobbed, whisked the tears away. “Read our minds…”

“Okay, okay, okay, stop waggling that thing at me.” Controlling her smile, Rebecca glanced across their faces. Her eyes caught Kaylene’s.

“Do. Your. Thing,” Kaylene said.

“Fine. Stop thinking about her,” said Rebecca. “She’s safe now. Mrs. Groch’s looking after her. And she’s got you, now. She’ll figure it out.”

“Fuck you, Rebecca,” Kaylene said, and burst out laughing. “How do you do that? I haven’t said one word about the Shelter to night. I don’t think I’ve said a word about it this whole week. I don’t remember saying one thing to you about—”

“She’s a witch,” Marlene said, through her perpetually exhausted Marlene-smile. “Do me.”

It took Rebecca a second, only because she wanted to check herself, make sure. Then she shrugged, nudged a strand of her own mousy brown bangs out of her eyes. “Too easy.”

“Oh my God, you bitch, you’ve got Twinkies,” Kaylene said, broke free of Jack’s arm, and dove for Marlene’s backpack. Marlene started to whirl, give chase, but there was no point. Kaylene was already elbows deep in Marlene’s backpack, shoveling aside organic chem textbooks, notebooks, calculator, tissues, until she came up with the crumpled pack in her fist. Strawberry flavor, tonight.

“Really?” Kaylene said, straightening. “You weren’t going to share these?”

“Actually, I wasn’t even going to open them, I don’t think. They just… called to me out the PopShop window.”

“Well, now they’re calling me.” Kaylene tore open the package and offered Marlene a piece of her own late-night snack. Marlene’s perpetual and permanent late-night snack. The secret, she claimed, of all-night cramming.

“My turn,” said Jack, putting his hands behind his back, standing at a sort of parade rest in his baggy shorts and blue bowling-team button-up shirt, with the dart sticking straight out from his head.

“You look like a unicorn,” she said, and Jack’s green eyes blinked, then flashed in his cookie-dough face. That was what he actually looked like, Rebecca thought. Not a unicorn, but a cookie. Purple-frosted, with spearmint leaves for eyes.

Over his shoulder, through the floor-to-ceiling windows, she could see the black gum trees melting into their moon-shadows along Campus Walk. The light from this room was practically the only light in the quad, which didn’t seem particularly strange at 1 a.m. in East Dunham, New Hampshire, in early August, with the great majority of UNH-D students still elsewhere for another few weeks. And yet, tonight, the dark looked deeper out there, for some reason.

Because I am so aware of this island in it, Rebecca thought, and felt herself fighting back tears again, grateful tears. Because I am so happy I washed up here. She glanced into the corner, saw Marlene’s hair spilling into Kaylene’s, red into black, as they elbowed each other and fought over strawberry Twinkie crumbs. Then they were up, laughing, Kaylene making biting-mouth motions over her fingers like a Ms. Pac-Man, burbling like a Dig Dug.

“Well?” Jack said. “Come on. What am I thinking?”

Focusing on the dart in Jack’s forehead chased the tears, instantly. But as soon as Rebecca lowered her gaze to his eyes, she blushed, without knowing why. Without wanting to think why.

“Come on,” said Jack.

Quietly? Nervously? Was that a little croak?

“Rebecca. What am I thinking?”

On the desk behind her, Rebecca’s computer pinged. Out of the corner of her eye, she saw Joel’s name pop up in its seemingly personalized, permanent chat window. Poor Joel.

“You guys go on,” she murmured, not quite meeting Jack’s eyes again. “Go play.”

“That isn’t quite what I was—”

“You weren’t thinking Human Curling? Tell me you weren’t thinking Human Curling.”

“Human Curling!” Kaylene whooped, dragging Marlene back between cubicles toward Jack.

“I can’t,” said Marlene. “You guys, it’s two weeks until school.” But she was only protesting out of habit, Rebecca thought. Duty. She was hardly even trying, tonight.

“Kaylene, let go.”

But now Jack had Marlene’s other arm. And there they stood in front of her. Her Crisis Center shift mates. Her every-single-day cafeteria meal buddies.

Her friends.

“Someone’s got to man the phones,” Rebecca said, ignoring the pings behind her as Joel tapped out his lonely messages from the kitchen worktable at Halfmoon House. He’d be sitting in no light, at this hour, Rebecca knew from long experience, from so much shared insomnia at that table in that house at these hours, the only sound the wind whipping leaves down the cracks in the gutters, owls in those trees, loons on the lake. Poor Joel.

But why would he be poor? Why did she always feel bad for him? Certainly, he never seemed to.

“Rebecca,” said Jack. “This is your Captains speaking.”

“Jack and the ’Lenes,” said Kaylene.

Even Marlene joined in, smiled tiredly. “Jack and the ’Lenes. Come on, Bec.”

“Not tonight,” said Rebecca, and wondered if she sounded as happy as she felt.

“Oh, it’s tonight,” said Kaylene.

“It’s tonight, it’s tonight, it’s tonight,” Jack chanted. “Why won’t you come? Seriously. It’s the middle of summer. It’s the middle of the night. It’s the middle of East Lake NoAssWhere, New Hampshire. No one’s going to call. And if they do, they’ll just get forwarded to the Hospital center. To, you know, professionals.”

“Who aren’t their peers.”

“Is it a money thing? How about if tonight’s on me? Rebecca, seriously, I know you don’t have—”

“It’s not a money thing,” she said, too fast, and halfhonestly. There was always the money thing, of course. But that wasn’t the reason. How could she even explain the reason?

Was there even one?

Only Joel. And the phones, which were supposed to stay manned at least another hour. And the fact that this feeling—this accompanied sensation—was still new in her life. And wading around too much in it—or setting out across it—felt foolhardy. Dangerous. Like testing fresh ice.

“You take Crisis Center rules pretty seriously, don’t you?”

“So do you, Jack. Or you wouldn’t be here.”

“The rules are not the Center.”

“We are the Center,” Kaylene said, and grinned at Rebecca. And… winked? Gestured with her chin toward Jack, and his ridiculous dart?

Then, somehow, the ’Lenes were shutting down their desk lamps, and Marlene had packed her backpack, and they were out the door, arms around each other’s shoulders, doing their leaning thing, first to one side, then the other. Their voices echoed down the empty corridor as they stomped and leaned their way down it, fluttered up staircases and sounded the silent classrooms overhead.

Jack, meanwhile, had shut down his computer, collected his supplies. But he’d dawdled, doing it, and now he paused once more in the doorway, his face half in shadow, the only remaining light coming from Rebecca’s lamp. He folded his faintly pudgy arms across his pudgy chest, which made him look twelve, like someone’s little brother, or else like a jester. A harlequin. And also like Jack.

“Is it me?” he said. “Is it my rad thrift- store blue bowling shirt?” He plucked at his pocket, with the name Herman stitched across it. “How about I man the phones, and you go Human Curling with the ’Lenes. You could use it. They’re good for you.”

“They’re good for everyone,” Rebecca said.

As if on cue, both ’Lenes appeared at the windows, on the path, standing together, joined at the hip. When they saw that she was looking, they did the lean. One side, the other. Kaylene beckoned, calling Rebecca out, into a world Kaylene was so obviously sure she belonged in.

And therefore, did? Rebecca wondered. Was that all it took?

“So it is me,” said Jack.

“It really isn’t.”

Unfolding his arms, Jack waved his fingers in front of Rebecca’s face as her computer pinged again. Joel, seeking contact. Jack’s fingers continued to wave in her face like a mesmerist’s. “Rebeccccaaaaa. You are getting very hungry. And thirsty. And Curly. You want to come play Human Curling with Jack and the ’Lenes.”

When Rebecca just sat, arms folded over the logo on her UNH-D hoodie, and smiled, he lowered his hands and stared into them, as though baffled that his spell hadn’t worked.

“Maybe tomorrow,” she said.

“Tomorrow,” said Jack. “You’re coming tomorrow. Plan on it. Book it in your Rebecca-Must-Plan-Everything-Years-in- Advance book.”

“I might,” she said.

“You just did.” Jack thrummed his dart, and it vibrated at her.

“Someone could really take that the wrong way,” Rebecca said.

“But not you, apparently.” Sighing, he smiled sadly—as sadly as Jack knew how, anyway—and left.

She watched the windows until he appeared. Instantly, the others adhered around him like charged particles, forming a nucleus. Kaylene glanced up once more at Rebecca, scowled, then waved. Jack waved, too, but over his head, without looking back. Then they were off, crossing from shadow to shadow down Campus Walk toward Campus Ave, where they’d skirt the forest, the edges of the little subdivisions full of tiny, mostly subdivided shingle houses, many of them empty for the summer, and make their way, at last, to Starkey’s, which had to be the only non-pub within fifty miles still open at this hour. They’d eat Mrs. Starkey’s awful canned-pineapple pizza, drink a pitcher of her Goose Island Night Stalkers: cranberry juice; white grape juice; seltzer; some rancid, secret spicy powder; and gin. And then, if Mrs. Starkey was feeling friendly, or else Jack waggled his magic fingers at her, she would give them the keys to the rink in the giant shed out back, and they’d grab brooms and push-paddles out of the cupboards in there and Human Curl to their hearts’ content.

It’s an orphan thing, she muttered inside her head, standing there in the dark. She was talking to Jack and his unicorn horn, but the phrase was Joel’s. Just one of the thousand things he had taught her during her four and a half years under his and Amanda’s foster care at Halfmoon House. That reluctance. That inclination toward solitude. You either have to learn to pay it no mind, or learn to mind it enough to do something about it. One or the other.

Like most of the things Joel and Amanda had taught her—most of Joel’s things, especially, she had to admit—that idea had made more sense back when she’d lived with them. Had seemed so comforting. It made less sense these days, or maybe just seemed too simple, not at all helpful, now that she lived on her own, had a little rented room she called home, even if it didn’t feel like home, yet. Not in the way she’d always assumed—been told—her own room would feel.

Stepping closer to the giant windows, Rebecca flicked on the lamp on Marlene’s desk. And voilà, there she was, out there in the world. At least, there was her refl ection superimposed over the path: little Chagall girl in a blue UNH-D hoodie, more pale-faced and mousy brown than glowing blue, but floating, anyway, up amid the lower leaves of the gum trees, her narrow face tinged green by the grass, blue by the moon.

Flicking off Marlene’s lamp, she watched herself vanish, then retreated to her own desk, pulled up a chair, tapped her sleeping computer awake.

RebeccaRebeccaRebecCaCaCaCaRebecca. Her name scrawled, and was still scrawling, across Joel’s chat window, as though he were tagging her screen from inside it.

Hiya, Pops, she typed.

Instantly, the scrawling stopped. The ensuing pause lasted longer than she expected. It lasted so long that she actually checked her connection, started to type again, then decided to wait. Around her, the whole building seemed to settle. Rebecca could feel its weight, hear its quiet.

Please don’t call me that, Joel typed. I’m not your dad.

I know. Don’t be ridiculous.

I know you know.

So don’t be ridiculous.

Pause. If she closed her eyes, Rebecca could see him there so clearly: his coal-black skin even blacker against whichever filthy white work T-shirt he’d worked in this particular day, the light from his laptop the only light in that long room, at that long wooden table. His wife gone to bed hours before, without bothering to tell or even locate him. His current foster kids—just two, right now, though he and Amanda generally liked to keep four at Halfmoon House, because that helped it feel more like a boarding school, which was exactly how Amanda wanted anyone she brought there to think of it—upstairs in their beds, possibly sleeping, possibly sneaking reading or headphone time of their own now that Amanda-chores and schoolwork were over.

On the lake, less than a mile away through the woods, there would be loons, Rebecca knew. The night-loons.

How’s Crisisland? Joel typed.

Empty, Rebecca answered, but didn’t like how the word looked. She deleted it, started to type Serene instead—which wasn’t quite right, either, just closer to right than “empty”—but Joel was faster.

SMACKDOWN??!!

Joel’s enthusiasm worked like Jack’s wiggling fingers, but was even more powerful, or maybe just more practiced. Or familiar, and therefore comfortable. And yet, what Rebecca typed back was, How’re my girls? How’s Amanda?

Tiring. Fine. SMACKDOWN??!! And then, before Rebecca could respond: I mean, the girls are tiring. Testing us. Amanda’s fine. I guess. Hardly saw her today, as usual. Working hard. Trudi still mostly talks to her socks.

Trudi was the newest Halfmoon House resident, one of the youngest Joel and Amanda had ever decided to bring there, barely ten.

She’ll come around. You’ll reach her, Joel. You always do.

Hey, R: maybe you could take her out rowing when you come tomorrow? Or—take her Human Curling!

Surprised, Rebecca straightened in her chair, her fingers on the keys. She thought about Amanda. Amanda would most definitely not be encouraging—or allowing—Rebecca to do any such thing with Trudi.

You know Human Curling? she typed.

I invented Human Curling.

Liar.

Okay, I didn’t. But you have to admit, I could have. It’s something I would have invented if your man Jack hadn’t.

Which was true, Rebecca thought sadly, staring at the screen. Human Curling was exactly the kind of thing Joel would have invented—and played, with everyone—if he’d had time. Or a wife who played with or even enjoyed him. As far as Rebecca had ever seen, Amanda just worked and taught her foster orphans how to survive the hands they’d been dealt and made rules. Like the one about seeing things clearly. Calling them what they were. And so, not calling Amanda “Mom” or Joel “Dad.”

Meanwhile, all unbidden, Rebecca’s fingers had apparently been typing. And what they’d typed was: Jack’s not my man.

Too slowly, again, she moved to delete. Again, Joel was faster.

A man after my own heart, your Jack. I do like your Jack, by the way. Fine man, your J—

SMACKDOWN! Rebecca typed, already opening the game site in a new window, calling up a string of letters for them to unscramble, make words from. READY?

What, for you? I don’t have to be ready for you, Rebecca. I barely have to be awake.

Rebecca grinned. Middle-of-the-night Joel. Checking in on his former charges, as he did almost every night, and which he had promised he would never stop doing until and unless he was sure they didn’t need him anymore. Talking trash to his computer in the quiet dark of his house. As alone as she was.

Can you feel it? she typed. That rush of wind? That’s me, surging past you.

You can’t win, Rebecca. If you Smack me down, I will become more verbose than you can possibly imagine.

Laughing, she typed her name into the left-hand SMACKER 1 box on the game site, waited for Joel’s name to appear next to SMACKER 2. Then the scrambled letters appeared, that awful, thudding cartoon hip-hop beat kicked in, the robot-Smackdown voice said, “Lay ’em down. SMACK ’EM.” And they were off. She got three words right off the bat, then a fourth, was typing a fifth, her fingers flying, when she realized her phone was ringing.

The Crisis Center phone. The one on her desk.

Joel, I’ve got to go, she typed fast into their chat window, and then closed it. She couldn’t have that open, didn’t want to risk distraction. He’d see eventually, whenever he looked up. He’d know what had happened.

And anyway, her phone was ringing. First time in weeks.

Rebecca had been working the Center too long to rush or panic. She allowed herself a moment to get centered and comfortable on her chair and in her head. Out of habit, her eyes flicked to the Quick Reference charts pinned to the cubicle walls, with their ALWAYS DO and DO NOT EVER lists, not that she needed them, or ever had, really.

You’re a natural, Dr. Steffen had told her, the first time she’d left Rebecca alone on a night shift. The best I’ve ever seen, at your age.

Switching off her lamp, settling into the dark, Rebecca picked up the receiver. When she spoke, her voice was the professional one she had mastered, had hardly had to practice: neutral, friendly, comforting, and cool. Anonymous. Almost exactly like her regular voice, she thought, then squashed that thought.

“Hello,” she said. “I’m so glad you called. To whom am I speak—”

“But should I?” said the voice on the other end. Sang, really. And then it made a sound.

Whistling? Wind? Was that wind?

Rebecca straightened, found herself resisting simultaneous urges to bolt to her feet and spin to the windows. Run from the room.

What the fuck?

“Should you have called?” Rebecca shushed her thoughts, commanding herself to relax as she leaned into the phone. “Of course you should have. It’s great that you called.”

“So it’s going to get better,” said the voice.

Was that a question? It hadn’t sounded like one. And… shouldn’t that have been her line?

One last time, Rebecca glanced at the Crisis chart. Then she turned away from it, relaxed in her chair. She was a natural, born for this if she’d been born for anything. “Starting right now,” she said.

Again came that sound on the other end of the line. Wind or whistling. Then, “I think so, too. Maybe you’re right. Maybe it’s time.”

“Time?”

“Is it good, do you think? Dying?”

Rebecca pursed her lips, made herself relax her hands on the tabletop. “Where are you?” she asked.

“High. Close.”

To the edge? To her? How would he know where he was calling, and why would she think that?

High, as in on drugs? Or in the air?

“The end. Lonely Street,” the voice whispered.

No. Sang.

“Is it beautiful there?” Rebecca heard herself say. Then she was staring, astonished, horrified, into the darkened windows, the shadowed summer leaves over Campus Walk. “I’m sorry, that was a really stupid question. What’s your—”

“It is, actually.” And he sounded surprised, her caller. Small, lonely, and surprised. “You know, it really is beautiful here. Hear it?”

Rebecca clutched the phone, watching the window as though it were a teleprompter that would tell her what the ALWAYS DO answer to that might be. Hear what? Nothing about this conversation was going in the direction it was supposed to.

But she was sure of one thing, or almost sure: this guy wanted to talk more than jump. Or what ever the hell he had been thinking of doing. So that was something. She would talk.

“What makes it beautiful?”

“The roofs,” he said. And he made a whimpering sound.

This time, Rebecca actually lifted the phone from her ear and stared at it. She wondered, briefly, if this were a pop inspection, some new Crisis Center supervision thing Dr. Steffen had invented. Then she decided it didn’t matter. Either way, she had a job to do.

“Roofs.” Nodding, though she had no idea at what, she leaned forward on her elbows. “That’s fantastic. What about them?”

“How far they are from the ground. The beautiful ground, where my Destiny would have walked with me.” Then he whistled, low and mournful.

It was like a song, almost, less what he said than the way he said it. Sang it. Was that why she had tears in her eyes?

“Listen. Why don’t you tell me your na—”

“And they’re all peaked! The roofs are. They have little attic rooms underneath, under the peaks. I just saw a little girl in one, with a night-light. She looked so alone up there in the middle of the night.”

“Yeah, well. Story of my life,” Rebecca murmured—as though she were dreaming—and realized she was blushing. Jesus Christ, was she flirting, now? Maybe she’d better stick to the chart, after all. “But no one has to be alone. Really. I should know. And I’m here with you.”

For answer, she got footsteps. Her caller, walking across whichever roof he’d picked to climb out onto. Then he whistled again, and went silent. As though…

Abruptly, Rebecca whirled in her chair, banging her knee on the desk as she took in the empty carrels surrounding her, the long, dark Crisis Center room, the linoleum corridor beyond it where the lights hadn’t flickered and nothing had moved.

Nothing at all.

On the other end of the phone, she heard neither whistle nor whimper nor breath. Swallowing her panic, keeping it out of her voice, she said, “Are you still there?”

“I think she’s gone to bed. Our little girl, in her attic room. All my girls have gone to their beds.” And there was that whimper again. Rebecca was almost certain he was crying, now.

“Except—” she started, but he overrode her.

“Except you.”

And suddenly—again—Rebecca had no idea what to say. Also for no reason she could understand, she wanted off of this call. And that made her feel like shit, and also rallied her. This guy wasn’t creepy; he was desperate. “You know,” she tried, slow and gentle, “one thing I really have learned, talking to people who phone here: no matter how bad you feel, no matter what you think you’ve done, it’s never too late to—”

“My Destiny killed my Mother.”

Rebecca stopped talking. She sat in the chair and waited. But her caller said nothing more. This was nothing new, she told herself, nothing she hadn’t dealt with before. So often, what the callers said didn’t make sense. And yet, the sense was there, if you listened. And the sense didn’t matter much, anyway. Not at the crisis moment.

And so, when she sensed it was time, she said, “I guess destinies do that to mothers. Sometimes.” She was leaning on her elbows again, pressing the phone against her ear, her mouth to the receiver. It was almost as though her lips were resting right against her caller’s ear. Her words didn’t even feel like words she would say; they were someone else’s words, pouring through her. “At least, that’s what I’ve been told. It’s what people told me about mine.”

Then she jerked, twitched her shoulders in alarm. Never, ever, insert yourself into a Crisis conversation. DO NOT EVER rule #2, right there in bold at the top of the chart.

“Then my Destiny’s mother killed her,” said the caller, and Rebecca gave up even trying to make sense of this conversation. She just listened.

But there was no sound in her building, and none on the other end of the line. The black gums waved silently out there, in a breeze she could neither hear nor feel.

“And yet, it’s a beautiful street,” she heard herself say.

To her relief, the person on the other end of the line whistled again; this time, there was no mistaking that sound for wind or anything else. “Yes it is,” said the voice. “You’re right. Again.”

“On a beautiful night.”

“So beautiful. Yes.”

“Full of people worth talking to, staying up late.”

This time, the silence felt different, seemed to yawn open against her ear: he-just-jumped silence. Panicking, Rebecca scrambled to her feet.

But he hadn’t jumped. “You’re very good at this,” he said, and then he said something else. “What you do.”

Or, Oh, you’ll do?

Rebecca pushed out the breath she’d been holding and closed her eyes, gripping the phone as if it were her caller’s hand. A hand she had somehow, in spite of all the mistakes she had made, managed to grab. “Tell me where you are,” she said. “I can have someone with you in five minutes. There are people just waiting to help. People who really want to help. Let me…”

The caller whimpered again. Unless that was giggling. Hysteria setting in.

“Will you let me send them?” Rebecca asked. “Please?”

“I’ll come see you,” said the caller.

And then he was gone. Rebecca could tell. He hadn’t hung up, just wasn’t there. Which meant he really had gone and…

“DON’T!” Rebecca shouted, grabbing uselessly at the edge of her desk. She waited for the splat. But none came.

And yet, her caller was gone. Had she just babbled some poor guy right off a ledge and out of the world?

Her eyes flew to the window, Campus Walk, the trees out there. Her own shadow, barely visible among them.

She’d lost one. Failed somebody, in the most brutal way one person could fail another.

She didn’t bother second-guessing herself or hesitating. She punched the speed dial on the Crisis phone and called the police.

Excerpted from Good Girls © Glen Hirshberg 2016